On multiple occasions, we have come across organizations trying to achieve their productivity goals or making management decisions that allow them to maximize the productivity of their teams and areas. Some examples of this are:

- CIOs looking to increase the rate of projects completed semi-annually or annually.

- Tech Managers making decisions to increase the amount of functionalities a digital factory can put into production.

- Managers or Leaders setting productivity goals for designs or mockups in their UX teams.

And it may seem like it’s the right approach, but sadly it’s not.

“In the era of knowledge and creative work, maximizing productivity can generate the opposite economic impact.”

Productivity in the Industrial Age

The general formula to determine productivity is total output/input, where:

- Output: Total value of goods produced in a given period (monthly, weekly, etc.)

- Input: Total value of resources used to produce these goods. These can be person-hours, raw materials, energy, etc.

Based on this, if a factory produces 5,000 goods per month, corresponding to 3,200 person-hours invested, then 1,562 goods are produced every hour, thus understanding the productivity per person-hour and allowing, based on this, to make management decisions that positively impact the factory’s productivity.

Making decisions to increase productivity, that is, increasing the number of goods produced and increasing the production rate of 1,562 goods every hour, makes a lot of sense and is what is required to maximize investment. But does it make the same sense if you are not a factory of goods?

What is the problem of productivity in the knowledge age?

Let’s establish the following premise, if I increase the amount of goods produced in a factory, keeping the same resources without impacting quality, the following happens economically:

- The unit cost of production decreased.

- I can improve the margin.

- I have more units per period of time to satisfy the demand (selling capacity).

These 3 points have a positive economic impact on the company’s income.

If we take the previous paragraph as a reference, what happens if we increase the number of projects completed by an IT area, mockups by a UX team, and functionalities that the digital factory puts into production? Are we generating a positive economic impact on the company’s income? The answer is NO, or not to be so harsh, not necessarily.

If we focus on increasing productivity, the following undesirable effects generally occur:

- Increase spending or investment without real visibility of the impact.

- It seeks to maximize the location or assignment of talent, which impacts the quality of deliverables and time to market and can also negatively impact people’s engagement by increasing turnover.

- It affects the value generated to the client, moving away from establishing a customer centricity approach.

In the era of knowledge and creative work, making decisions based on industrial productivity leads us to make bad economic decisions. To make economic decisions, we need to focus on the effectiveness of ideas, that is, how effective our ideas, initiatives, projects, etc., are to get closer to our goals or move the metrics that matter.

Let us consider the following hypothetical cases:

- Bank “X,” in the technology area, has completed 120 projects this year, and in the last 3 years, it has increased its productivity by 20%. They are proud of the number of projects completed, which is one of the area’s success metrics.

- Bank “Y,” in the technology area, has completed 90 projects this year, where 15 enabled the business to improve its market share by 5% and 10 reduced operating costs by 5%.

We cannot say that Bank “X” has made good economic decisions with the information we have. They have carried out more projects and probably increased their portfolio’s budget. Should they continue to increase their project completion rate next year, or should they do something different?

Bank “Y” knows how effective the technology projects were. However, it does not make sense to increase the productivity or number of completed projects annually, that is, to do more than 90 next year. On the contrary, they should increase the success rate and effectiveness, seeking that next year, there are not 25 projects, only those that move the needle.

The principle we seek to establish is “start less, do more.” Organizations and teams in the knowledge era need to start fewer initiatives, projects, and developments but seek to generate more impact and be more effective with those they start.

“Not calling software development teams factories is the first step to move from productivity to effectiveness and make better economic decisions.”

Suppose they need to measure the value generated by your initiatives, functionalities, etc. So you need more information to make effective economic decisions; that is where we have the first element missing in organizations.

Each stage of the project, functionality in production, experience, or service placed in the hands of the client needs to measure its value and impact from day one. Knowing the value and impact lets us know if it was a good idea to start an initiative, if we needed more evidence, or if experiments or small pilots were necessary before investing more money into a larger initiative.

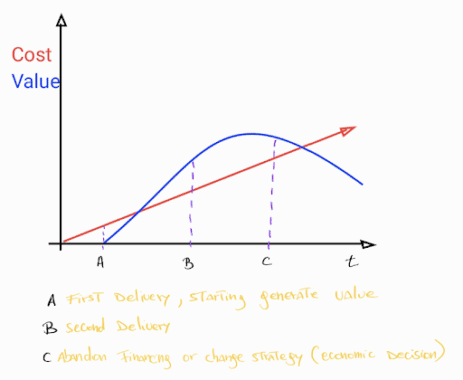

The best way to measure the impact or value of initiatives is to make small initiatives. If a project takes one year and involves many resources, and only at the end of the year can I begin to measure the impact, it is a bad design with a high economic risk. A better approach would be to divide the project into 4 well-designed deliverables. At the end of each deliverable, for example every 3 months, measure the value and decide whether to continue investing in the project.

An organization that finished 30 impactful projects and re-invested the funds from 40 canceled projects is more effective than 70 finished projects with no measure of success.

I invite you to answer the question: Is your organization productive or effective? Learn more about our Process Optimization Studio.